In my previous post, I wrote about Huntington Hartford’s

iconoclastic views on art and his art collection. As he planned a museum to showcase the art he

favored, he needed a building in Manhattan.

Once built, the museum building received a mixed reaction from critics,

just like the art that was on display inside.

The Site

Hartford faced a daunting task when deciding to place his

new museum in New York City. New York

has dozens of art institutions and galleries, so making an impression (both

then and now) is difficult. Hartford

chose a prominent location for the museum, and it was a location that would certainly get noticed. But, the lot he chose posed some very

specific problems.

Columbus Circle sits at the southwestern corner of Central

Park. Serving as the intersection of

Central Park West and Broadway, it’s about as high-profile a location you can

get in Manhattan. The plot of land at 2

Columbus Circle is where Hartford decided to build. It’s a small, trapezoid-shaped bit of land

surrounded by busy streets. In another,

less populous city it might have just remained undeveloped green space at the

edge of a traffic circle. But, in

space-starved Manhattan, something was built there. A structure housing "a shoe store and offices" (according to Hanford Yang's proposal- see below)

sat on the property when Hartford bought it in the late 1950s. To any architect, the plot would be difficult

to build on. It was small (only 5,000

square feet- miniscule by New York standards) and oddly shaped. Each side of the property was a different

length, and the longest side was only about 100 feet. Any architect that Hartford chose would have

to deal with these limitations while still providing ample space inside to show

the artwork sufficiently. Hartford

eventually chose Edward Durell Stone as the architect of the building, an

experienced builder who approached the site and the museum in some pretty

interesting ways.

Choosing an Architect

|

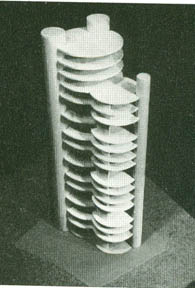

| Hanford Yang's design |

When searching for a designer for the future Gallery of

Modern Art, Hartford was initially drawn to the design submitted by a recent

MIT graduate named Hanford Yang. Yang,

who was Chinese, proposed an innovative design (it was actually his Master’s

thesis) that used three tall tubes, placed at the edges of the property, to

house the mechanicals and stairs. This

left the interior spaces open. In Yang’s

design, the exhibition floors were hung from the three tubes and sheathed in

plastic panels that acted as walls. While

researching this topic, I was surprised to find Yang’s entire original proposal from 1957 posted on the Internet. It’s a

fascinating relic from the past, documenting his unrealized concept as well as

giving a contemporary account of 2 Columbus Circle before the museum was

built. But, Yang was not registered as

an architect in New York State, so his design could not be used. Hartford eventually brought in Edward Durell Stone as architect, an American designer with extensive experience in

museums and public buildings.

|

| Stone's American Embassy in New Delhi, India |

Stone was no stranger to museum design. He had designed an expansion at the nearby

Museum of Modern Art, and was at the time receiving international attention for

his designs of the US Embassy in New Delhi, and the US Pavilion at Expo ’58 in

Brussels. He also designed such notable

buildings as Radio City Music Hall and the Kennedy Center in Washington DC (I discovered while writing this that he also designed the Buffalo News

Headquarters. I drive by this building

almost daily and never realized Stone was the architect. You truly do learn something new every day!).

At the time, Stone’s buildings were

characterized by delicate, perforated screens that covered a building’s entire façade,

making it seem light and airy. These

screens became a sort of trademark for Stone, and would prove difficult to integrate into the final Gallery of Modern Art plan.

The Building

Stone faced many challenges while designing the GoMA. Art needs wall space, but interior spaces also

need light. Bringing large amounts of

natural light into the museum wasn’t really an option, since windows take up

wall space. Therefore, most of the light

in the GoMA had to be provided artificially.

The windows were small, porthole-shaped

openings that were pushed to the edges of the structure, allowing only limited

natural light to reach the interior.

From the outside, they were covered by Stone’s trademark perforations.

|

| The GoMA's interior. The small porthole windows can be seen in the background. |

Inside, Stone handled the space restrictions quite

elegantly. The museum was constructed

with nine floors, but only four floors showcased the art. When planning the exhibition spaces, Stone

had to contend with such things as mechanicals, elevator shafts, and

stairways. These essential elements can’t

be removed from any structure, so Stone had to figure out a way to work around

them. The size of the stairs between the

exhibition floors was expanded, creating large stair landings. These landings also served as gallery space,

greatly increasing the amount of wall space available. The wall spaces were decorated with exotic

hardwoods and the floors were carpeted.

A far cry from the stark white walls popular at the Museum of Modern

Art. The effect was more like being in

someone’s living room instead of a sterile museum. A pipe organ provided live music for patrons

as they strolled through the galleries.

The remaining floors housed offices, a small café, and Hartford’s lavish

Polynesian restaurant, named the “Gauguin Room”.

|

| An early rendering of the GoMA |

But at ground level, one could find what were perhaps the

buildings most characteristic features (for better or for worse). Stone designed the museum as sort of a stretched-out

Venetian palazzo, supported by columns with round windows above them. Critics were quick to compare the shape to

lollypops, and the building was unofficially called the “Lollypop Building” for

decades afterwards. The features of the

building were either wildly ahead of their time or just plain comical. The building has been described as slyly

referencing other architectural styles; a precursor to what later became known

as Post-Modern Architecture. To others,

it just looked silly. A white elephant

stranded at the edge of the traffic circle.

Critics were divided as to whether Stone had created a modern

masterpiece, or was signaling that his best work was now truly behind him.

|

| The lollypops are clearly visible here |

Legacy and Renovation

Hartford spent a considerable amount of his own money to construct

Stone’s design. The building, which had

been budgeted at about 3 million dollars, ended up costing over twice

that. The Gallery was open for about five years, and Hartford failed to recoup his investment. The lukewarm reception of both the

art and the building that housed it hastened its closure. By July of 1969, the GoMA was finished. The museum had failed to make an impression

on the New York art world and Hartford transferred ownership to Fairleigh Dickinson University, who operated the site as the New York Cultural Center. The building survived long after the Gallery

of Modern Art was dead and buried, and slowly became a part of the fabric of

New York City. Manhattan residents

remained divided as to its legacy, though, and several efforts to get the

building landmark status failed. In

2008, The Museum of Arts and Design (formerly the American Craft Museum) moved

into the building and radically changed both the interior and exterior. This touched off numerous battles between

preservationists and architecture scholars who wanted to save the building as

Stone designed it, and developers and planners who wanted something done with

the structure regardless of what it looked like (it had been unoccupied for many years at that

point). I won’t re-hash the arguments

here, but a good version of the events can be read here.

Architect Brad Cloepfil was hired to adapt the building for

the 21st century. The marble

cladding was removed from the entire structure and replaced with windows and

ceramic panels. The interior was

redesigned as well. The lollypop columns

at ground level were kept, though now they are sheathed by glass panels.

Both the art collection and the museum are gone now,

relegated to the category of Cultural Ghosts.

Photographic evidence is all we have left to remember them by. Stone’s building design, which stood for

decades, appears in photos and films (people do occasionally make movies in New

York). Huntington Hartford didn’t make

out so well. He died mostly forgotten,

his art collection long dispersed. The

museum building held up much better, now silently joining the ranks of such

lost buildings as the venerated Penn Station.

It is gone, but not entirely forgotten.

|

| Stay Puft Marshmallow Man included to show scale. |

Next week, some concluding thoughts as I wrap up another topic.